Remember when I sent out a call for guest posts? I’ve decided to start posting them now, while I put the finishing touches on my latest Bookstore offering, Navigating Ethics and Bias. Today’s post comes from Kory Cerjak, an up-and-coming writer who blogs at The Fandom Post and Deconstructing Comics (both links go to recent posts of his). Kory sent me a rough draft which I put through a few editing rounds. I made some grammatical and flow edits, but the sentiments are all his.

Guest posts on Otaku Journalist are not necessarily posts I agree with 100 percent. Instead, they’re an opportunity for aspiring writers to share their thoughts on otakudom and get some more exposure for their writing on fandom topics. Please comment on them like you would on any other post on this blog!

What better a topic for Otaku Journalist than otaku comparisons?

In particular, I’m talking about the differences of otaku subculture as portrayed in Genshiken compared to in Oreimo. Up until now, I’ve never had a reason to formally write about it. But I’ve been given that opportunity by Otaku Journalist, so let’s jump right in.

Genshiken is about embracing your inner otaku. Protagonist Sasahara is a normal guy who likes otaku things and tries to love them outwardly. But he’s no Madarame (a hardcore otaku) or Kousaka (a guileless purveyor of hentai). Sasahara is embarrassed about buying figures of girls and doujinshi. There’s a great scene where he’s fighting with himself about whether he should buy a doujinshi, not just because they cost money and he’s a poor college student, but because he doesn’t want to be seen buying the doujinshi! That’s the big difference: any shame the characters of Genshiken feel about being otaku comes from within.

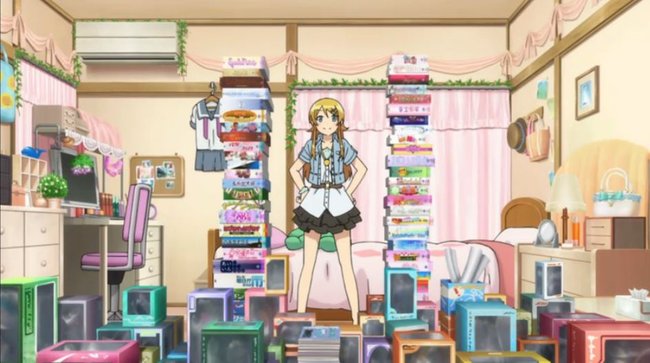

Meanwhile in Oreimo, Kirino is completely comfortable with her own otaku passions. Only problem is, she has no one to talk about it with. But while she’d find ready co-conspirators in the Genshiken group, the world of Oreimo doesn’t look so kindly on Kirino’s hobbies. Instead, Kirino’s parents and best friend are “normal” people who view anime as evil. It’s not until Kyousuke comes along to defend anime and eroge that they see the light. In Genshiken, you don’t need a Kyousuke character. Even Genshiken’s foil character—Kasukabe—is indifferent, not hateful, toward anime.

But while Kirino has infinitely more outward reasons to feel ashamed of being otaku, it’s Genshiken’s Sasahara who struggles with his identity the most. By the third episode of Genshiken, when Sasahara’s at Summer Comic Market, he still feels uncomfortable even when he’s surrounded by thousands of people with the same interests as him. I felt the same way at my first anime convention—it’s very humbling to find out that you’re not the only one that likes this weird niche thing called “anime.” And that’s really what Genshiken is about. It wants to take you on Sasahara’s journey from closeted otaku to full-fledged, doujinshi-buying anime fan.

The fourth episode of Oreimo is also at Summer Comic Market (it’s even raining in both of them!). But where Sasahara was still trying to accept himself as an otaku, Kirino already has. She’s trying to find other people to be otaku with her, and she’s still learning whether new friends Saori and Kuroneko are on her level. They’re still in that awkward new friend stage where you’re not quite sure how the friendship works yet, and Kirino’s tsundere character doesn’t help matters much. The episode isn’t about embracing yourself, but learning to embrace people who have the same tastes as you.

It’s clear to see one major similarity between Oreimo and Genshiken—they’re both shows made by otaku, for otaku. However, each show goes about targeting the audience in a vastly different way. Genshiken’s characters are relatively realistic otaku types, and it’s not much of a challenge to relate to them and see parts of yourself. Oreimo goes the moe route, presenting otaku caricatures inhabiting the bodies of pretty girls. It’s far more likely you’d encounter a Sasahara than a Kirino in real life, to be sure!

The differences to us otaku, however, are largely moot. We look for a different kind of audience surrogate and we find that in both anime. There’s no singular otaku anime because there’s no singular otaku experience. We can compare portrayals all day long, but in the end there’s room for both.

1 Comment.

Am I the first to post? Alright here it goes. I love the series Oreimo and Genshiken. Its helping me understand my inner otaku even and has opened my world somewhat. To quote Genshiken “What I lack is the courage to accept myself for who I am”. Its a stellarly deep quote for a manga huh?