I’ve been feeling overwhelmed lately, and my recent anime choices have reflected that. I’ve been dividing my viewing time between two calming, spirit-filled if not spiritual, shows.

First I was rewatching my 2013 favorite, Natsume’s Book of Friends, a staple I always turn to when I need a pick-me-up. Then, a friend recommended I check out the similar Mushi-shi.

I mistakenly thought the OVA and second season, both on Crunchyroll, were all of the show that existed. It was pretty exciting when I discovered the Season 1 S.A.V.E. DVD on Amazon. Now I’ve watched both shows in full—several times if you count some of the episodes.

Mushi-shi is like a creepy Natsume’s Book of Friends without any of the warmth.

— Lauren Orsini (@laureninspace) April 28, 2014

This is what I tweeted after my first episode of Mushi-shi. They’re so similar, so I decided to write down my feelings and figure out why I see them so differently.

Both series center on a young man who has the unique ability to see spirits that inhabit our world. In Natsume’s case, those are ayakashi straight out of Japanese folklore; in Ginko’s, they are mushi, a fictional form of life somewhere between plant and animal. It is unusual for Ginko finds a mushi human enough to talk to, and very rare that Natsume finds a yokai who can’t.

Natsume’s Book of Friends is all about the problems of the yokai themselves, and Natsume does his best to help them find solutions. Ginko, on the other hand, assists people who have fallen on disaster by accidentally crossing paths with mushi. In Natsume’s world, ayakashi can be good or evil or a mix of the two. In Ginko’s, mushi aren’t good or bad, just trying to survive. Mushi aren’t governed by morality, just the often harsh laws of nature.

Sometimes, Natsume crosses paths with other people who can see what he sees—the exorcist Natori, the antagonistic Matoba clan. Other times he spends time with friends who have a touch of his gift, or can only sympathize, like Taki and Tanuma.

Meanwhile, Ginko interacts with somebody who can see mushi almost every episode. The human victim of a mushi is able to temporarily see the mushi that plagues them. It’s apparent that other mushi-shi, people who do what Ginko does, also have the gift. However, Adashino, who is portrayed as Ginko’s old friend, is fascinated by but unable to see mushi.

What makes Natsume so charming and Mushi-shi so dark? Natsume’s tragedies lie in the past while Ginko’s are always looming, ever-present and ready to consume the show.

Natsume focuses on the tragedy of Natsume’s lonely past, made dim by the close friends and family he has in the present. There are clear antagonists with clear motives, and it’s obvious who the good guys are, too. Every episode has a happy, or at least bittersweet, ending.

On the other hand, death and loss are not glossed over in Mushi-shi. The worst part is that, because mushi are rarely sentient, there’s nobody to blame for the tragedies. Ginko visits the occasional friend, but mostly he is alone, a traveler. And because of his unique tendency to attract mushi, he is condemned to wander forever.

Natsume is portrayed as a formerly very lonely person. But in the show, Natsume is always talking to people who love him—family, friends, and yokai. For him, loneliness is something that can be overcome. For Ginko, never. The people Ginko meets need him, but he can never stay in one place long enough for them to get to know him or—of all impossibilities—love him.

Natsume has grown adept at putting up walls around himself, but the people around him have grown adept at breaking through. Ginko doesn’t need to try to keep himself aloof; his lifestyle guarantees it. Loneliness pervades both shows to be sure, but the difference for me is how permanent it remains in Mushi-shi.

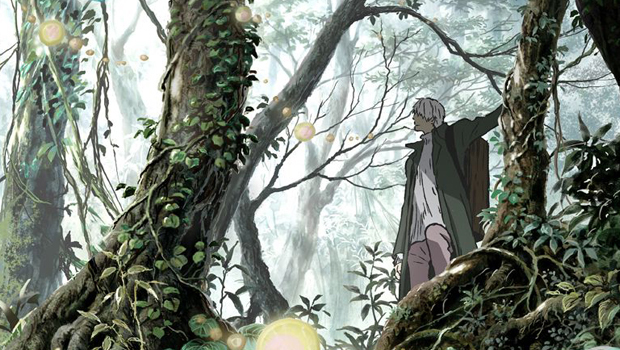

These are both great shows to watch quietly before bed. The pastoral, sylvan atmosphere and gentle music makes each one strangely calming. Supernatural intrigue takes the stage, but the real theme shows through the cracks—how isolation can mold and change a person.

Screenshots in order via Natsume’s Book of Friends, Mushi-shi.

Discover more from Otaku Journalist

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

7 Comments.

Mushi-shi is fantastic, one of my favorites. The manga is just as good, very dream like. There was also a live action directed by Katsuhiro Otomo but I have not had the chance to watch it yet.

Did not know about the live action! I’ll have to check it out. “Dream like” is exactly the way to describe Mushi-shi.

If memory serves correct Mushi-shi will be taking a break during the summer and return in the fall for the second half of the season.

My personal “cheer me up” anime series is Minami-Ke. A season or two of that show always helps.

Now if they’d just release it in the US. I want to buy it as I love it so much and get so much out of it. I really, really want to give back to people who made the anime and four season at that. Plus a couple of OVAs. Or at least have it on Crunchyroll so I can give something, anything back. No manga release in the US either. *sigh*

What I like about “Mushishi” is precisely that feeling of distance and isolation, which comes across to me as inchoate longing. Most stories are about a character or a plotline, but rarely a mood or a feeling, which may explain why I liked it so much.

And with that I think I have a lead-in to my eventual discussion of Mushi-shi.

Yes, I would love to read that, Serdar! About a mood or feeling more than a plot… That’s such a great way of putting it.

That’s … uh, quite off-mark. Ginko may be a loner, but he is far from alone. He enjoys this lifestyle. Actually, he is such a born traveler that the fact he attracts mushi is more of an excuse than something that troubles him in any way. I think it’s pretty small-minded to just write this off as about “isolation”. Heck, even YKK was more about isolation than Mushishi…